Originally published 27 September 2016

A few years ago, I was sitting in an auditorium with hundreds of senior military and police commanders at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. We were listening to a motivational talk by a well-respected national speaker. While remarking on the nobility of military and police service, the speaker said to the group, “You are simply a better class of people.” The comment appeared to be designed to motivate and inspire the attendees, but it caused me to reflect deeply on the unstated message. I began to wonder about the possible implications of telling a group of strong, dedicated people, who swear an oath to defend the Constitution, that they are essentially better than those they serve.

I am confident the speaker, whom I know to be an intelligent and deeply passionate person, had the best of intentions. What concerns me is the manner in which some police officers internalize the message. There are unintended consequences to seeing ourselves as better than the people we serve. When we shift our focus to the imagined superiority of our group—the elite, the entitled, we who are deserving of special consideration because of our superior character, ethos, and sacrifice—it can manifest as disdain for others we view as less deserving. This mindset invites contempt and abuses of power, the likes of which have been captured on video and played out in the national media, helping to fuel anti-police sentiment. Further, when protectors deem those who are protected as unworthy, it represents a direct threat to democracy.

In the past several years, it has become popular in police training circles for trainers to use metaphors to characterize law enforcement’s relationship with the public. Among the most popular of these is the “sheep/sheepdog” allegory. Trainers who favor this sort of framing explain that many members of the public are like sheep that operate in constant fear of predators, while law enforcement officers serve as the sheepdogs that protect the hapless sheep from the wolves (criminals) that stalk them. While this type of contrasting might seem harmless, it actually objectifies both the police and the public they are sworn to serve in ways that undermine police effectiveness and helpfulness.

A sheepdog’s job is to ensure the integrity of a herd. When the herd gets out of line, the sheepdog drives them by growling and nipping at their heels. The sheepdog adopts a posture characteristic of a predator—like a wolf, for example. This transformation puts the sheep in a perpetual state of fear of being singled out and attacked, thus providing an extrinsic motivation for them to fall in line. Sheep are afraid of sheepdogs just as they are afraid of wolves. They don’t trust them and only comply because they are motivated by fear of consequence. Sheep aren’t equipped to fight their antagonists, so a growling sheepdog may not invite escalated dangers amongst the sheep. Not so with people, however. Among those being growled at are people who are capable of resisting. The sheep/sheepdog allegory completely misses how growling sheepdogs can motivate and escalate resistance.

Furthermore, characterizing people as helpless sheep creates a false sense of reality. It helps foster a “sheep” mentality that indirectly states, “If you have a problem, do nothing. Call 9-1-1 and let the professionals handle it.” The fact is there are many people in our communities who are impressively tough and capable. Even though they do not serve as police officers or soldiers, they are quite prepared to protect themselves and others. Even people who lack this capacity still possess the power to keep their eyes open for suspicious people and dangerous circumstances and report what they see to the authorities. Given the capabilities that people in our communities possess, we should be doing all we can to develop partnerships with these folks, not alienate them.

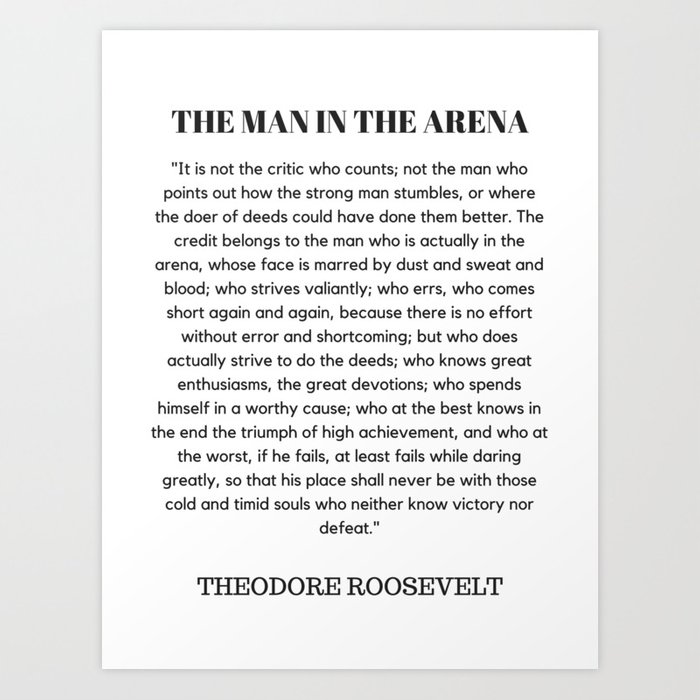

The hyperbolic use of the term “warrior” represents another way law enforcement culture has worked to emphasize distinctions between the public and the police. Metaphors can illuminate, but if taken overly seriously, they can also mislead. The warrior archetype is one of the most misunderstood models in present-day society. While noble ideals like service and sacrifice were often revered in ancient warrior cultures that are celebrated in current law enforcement trainings, other elements of those same cultures would be disastrous if applied today—for example, the eating of pig’s blood gruel, shame-based ritual suicide, and strategic murdering of members of slave populations in order to prevent rebellion. It is as difficult to imagine today’s police officers celebrating these types of things, as it is to imagine ancient Spartans petitioning their labor organization to help block the implementation of mandatory physical fitness standards. Elevation of the warrior ethos as ideal without thinking more carefully about the elements of that ethos that we subscribe to and those that we don’t, can blunt the effectiveness of warrior-focused training approaches.

For many of the people I speak with who promote external concepts of warriorship in law enforcement, the battles they can’t seem to win actually are internal rather than external. For example, they often are overcome by justifications for not training their bodies and expanding their minds. They fear the influence of alternative perspectives because, deep down, they question the strength of their own convictions. They create a fool’s choice in their minds between being compassionate and being tough and capable.

Unless you are an active member of the military, the warrior ethos is most practical when applied in the context of fighting the internal battles against our own individual biases, fears, prejudices and loyalties that cloud our ability to see and act on what is right. Certainly, in some of the oldest warrior literature the “enemy” the text referenced was understood to represent these types of personal traits, and the battlefield was considered to be one’s own heart.

The warrior ethos can be a powerful driving force in intrinsically motivating police officers to remain mentally, physically and spiritually trained, skilled and prepared to act courageously in challenging circumstances. However, it is generally not helpful when used to characterize a police officer’s outward posture toward the public he or she serves. Historically, warrior cultures have not always functioned with their societies best interest in mind.

We, whose work makes us society’s protectors, are not better than the people we serve. Our own acts of misconduct demonstrate this. And the frequent acts of police heroism don’t make us better either. Our communities are filled with heroes that don’t wear uniforms. We, the police, are not better than society; we are part of and a reflection of our society. If law enforcement officers and organizations happen to behave better (and sometimes they don’t) it is because policing organizations are generally well led and driven by an others-centric professional ethos. Any police officer that is at war with his or her fellow community members is at war with him or herself, who is but a member of the community. Such officers have perhaps elevated the metaphors they have been trained in above their fellow community members they are sworn to serve. Their closely-held metaphors may be blinding them to the equal personhood of those with whom they interact. The police should, and most often do, use lawful force and the power to arrest only in the service of protecting the Constitutional rights and personal safety of others.

In order to foster safe and responsible society, police need to see themselves and others as they are—as people. The work of terror organizations, extremists and mass shooters is facilitated when society is divided into marginalized and dehumanized groups. I think most police trainers have the best of intentions when discussing the warrior mindset. The majority of men and women promoting these concepts are admirable and have dedicated their lives to helping police officers stay safe so they in turn can serve the public honorably.

One of the biggest challenges our society faces is carving out a legitimate place in modern law enforcement for the aspect of the warrior ethos that enables police officers to rise to the challenge when they find themselves in “kill or be killed” situations—like the tragic cases of cops being murdered in ambushes. While these incidents are rare, community-minded officers have to possess situational awareness since it’s not always possible to predict when they will occur.

I am not arguing that we should turn away from trainings—whether they use “warrior” metaphors or others—that prepare officers to respond effectively to violent attacks. On the contrary. Rather, I am arguing that we should prepare our protectors in the capabilities needed to effectively deal with the worst of circumstances while doing so in ways that don’t set our officers up to respond poorly in other circumstances. Training that is built on misleading metaphors sets officers up to provoke aggression in situations where patience and deliberate thought would be more effective.

Training officers that everyone is out to kill them can make officers fearful, paranoid and overly aggressive. Ironically, this type of hypervigilance can make officers less likely to train properly to overcome rare cases of extreme violence and more likely to retreat to the comfort of a sedentary life style, which might help explain the epic proportions of obesity and general poor health that afflicts many police officers today.

At times, police work can be frightening, and believing that one is prepared to deal with formidable threats can be comforting on many levels. However, comprehensive safety isn’t achieved by platitudes, overly simplistic metaphors, and aristocentric idealism. Comprehensive safety is achieved by a strong commitment to mental, spiritual and physical preparedness that facilitates the confidence to build and leverage trusting relationships with the people who need the police the most.

We haven’t seen the last of unprovoked, violent attacks on members of the public and law enforcement, and a principal aim of policing agencies should be to recruit more and more community members to be vigilant, have agency, and feel a sense of partnership with the police. Law enforcement in a democracy is at its best with an ethos where officers see themselves as an integral part and reflection of the best nature of the society they serve, not as a morally superior caste set above that society.

Charles Huth serves as the Past-President of the National Law Enforcement Training Center, a not-for-profit corporation dedicated to delivering effective training to law enforcement, corrections, security and military personnel. Charles is a Captain with the Kansas City, Missouri Police Department and has 25-years of law enforcement experience. He currently serves in the Chief’s Office as the Staff Inspection Officer. He is a former team leader for the Street Crimes Unit Tactical Enforcement Squad, and has coordinated and executed over 2500 high-risk tactical operations. Charles is a certified national trainer in defensive tactics, an expert witness in the field of police operations and reasonable force, and a Subject Matter Expert on police use of force. He has a Bachelor’s Degree in Multi-Disciplinary Studies, and an Associate’s Degree in Police Science from Park University.

Charles is an adjunct professor for the University of Missouri—Kansas City, and a part-time instructor at the Kansas City Missouri Police Leadership Academy. He serves as a consultant for the KCPD’s Office of General Counsel, the Missouri Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission, and the Missouri Attorney General’s Office. He is a member of the International Law Enforcement Educators and Trainers Association and the National Tactical Officers Association. He is the President and CEO of CDH Consulting L.L.C., a law enforcement consulting and training company, and a Senior Consultant for The Arbinger Institute, an international corporation specializing in conflict transformation.

Charles has 35-years of experience in the martial arts, with a background in competitive judo and kickboxing. He is the coauthor of Unleashing the Power of Unconditional Respect-Transforming Law Enforcement and Police Training-CRC Press (June 2010). He is a veteran of the United States Army and lives in Kansas City, Missouri.